In today’s cyber threat landscape, almost everyone is one bad day away from a security incident. While not every incident becomes a data breach, security teams need to be prepared for anything. Just like that one friend who has a spreadsheet to help them organize the minute tasks associated with a project, security teams need to have a prepared list of steps to take during an incident.

While your incident response plan acts as the overarching strategy, your incident response process outlines the steps and documentation necessary for investigating, containing, remediating, and recovering from an incident more efficiently.

What is an incident response plan?

An incident response plan is a strategic, step-by-step guide that defines security analyst responsibilities and outlines actions they take during an incident. The incident response plan will include policies and procedures for:

- Preparation: testing processes

- Identification: building detections

- Investigation: tracing suspicious activity to compromise assets

- Containment: strategies for preventing additional damage

- Remediation: identifying root cause and fixing impacted systems

- Recovery: restoring affected systems to pre-incident state

- Lessons learned: reviewing incident response for any potential areas of improvement

What are the differences between an incident response plan and incident response processes?

Although the incident response plan and the processes inform one another, they are different and serve different purposes. The plan provides a framework for how organizations define the processes.

The incident response processes are the ongoing, continuous activities for managing the incident response life cycle from risk assessment and incident handling to lessons learned and continuous improvement.

What are the primary incident response frameworks?

Incident response frameworks provide the structure for the organization’s processes. Both the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and the industry organization SANS Institute have frameworks based on cybersecurity best practices. Additionally, the OODA Loop, which stands for Observe, Orient, Decide, and Act, has gained popularity in recent years.

NIST Special Publication 800-61r3

In April 2024, NIST released the initial public draft of “Incident Response Recommendations and Considerations for Cybersecurity Risk Management,” the update to its 2012 “Computer Security Incident Handling Guide.”

To better align with NIST Cybersecurity Framework (CSF) 2.0 Functions, the agency updated the incident response framework by treating it as a continuous feedback loop rather than a linear process. The original NIST incident response framework outlined the life cycle as follows:

- Preparation

- Detection and analysis

- Containment, eradication, and recovery

- Post-incident activity

In the original model, a continuous feedback loop existed between detection and analysis and containment, eradication, and recovery. Security teams were expected to update the preparation stage only after reviewing post-incident activity, like lessons learned.

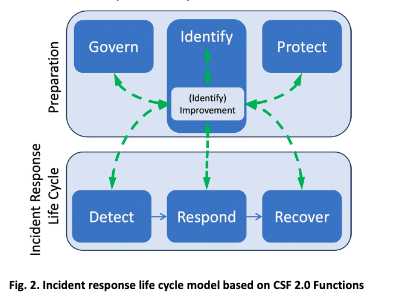

Under the new model based on the six CSF 2.0 functions, the incident response framework now clearly separates Preparation as the ongoing daily activities of a security program, consisting of the NIST CSF 2.0 Govern, Identify, and Protect functions.

The incident response lifecycle phases focus on the Detect, Response, and Recover functions. However, unlike before, all functions continuously inform one another.

Within the Detect, Respond, and Recovery Functions, NIST focuses on more than thirty High Priority CSF elements.

SANS Institute Incident Handler’s Handbook

Although the SANS Institute Incident Handler’s Handbook is organized differently, it contains similar steps. SANS identifies the following parts of the incident life cycle:

- Preparation: Establishing policies, creating a plan/strategy, communicating the policies and processes, documenting the incident, assigning responsibilities, providing access controls, choosing tools, and training responsible parties

- Identification: Detecting anomalous activity in the environment and reporting it to the responsible parties

- Containment: isolating the threat and affected systems to reduce impact

- Eradication: removing malicious content from systems and remediating vulnerabilities that attackers exploited

- Recovery: bringing affected systems into production environment after testing, monitoring, and validating them to verify that they have not been reinfected or otherwise compromised

- Lessons Learned: summarizing and reporting on who detected the incident, when they detected it, its scope, process for containment and eradication, recovery activities, areas of effectiveness, and areas of improvement

The OODA Loop

Although John Boyd originally developed the OODA Loop for the military, security teams increasingly apply it to cybersecurity incidents as a decision-making framework. The OODA Loop focuses on four actions:

- Observe: monitor for abnormal activity

- Orient: apply threat intelligence to gain situational awareness

- Decide: identify next steps to minimize damage and recover quickly

- Act: contain threats, remediate affected systems, recover affected systems, review response effectiveness

Checklists to Help Security Team Organize Incident Response Processes

With the right detections, you can identify a security incident. For example, if you build high fidelity Sigma detections aligned to the MITRE ATT&CK framework, you can get started investigating the incident, remediating the systems, and recovering from the incident faster.

The last three stages of the incident response lifecycle often require hands-on-keyboard tasks. Without well-defined processes, security teams often struggle to risk-rate alerts appropriately which can have a cascading delay effect across the entire incident. The longer the triage, investigation, and containment phases take, the more time attackers have to do damage to the environment.

To get started thinking about what processes you need, you may want to consider the following checklists.

Triage and Investigation

During the triage and investigation phase, you need to make fast decisions about:

- What the alert tells you

- How much impact the potential incident could have

- What caused the incident

During this phase, you should engage in the following activities:

- Prioritizing incidents based on impact to continued business operations

- Assigning responsibilities in a ticketing or tracking system to prove oversight and governance

- Gathering forensic evidence to identify the incident’s root cause

Some critical activities include:

- Performing initial incident analysis to understand the incident’s nature and potential impact

- Assigning an incident severity level using predefined criteria to prioritize response activities

- Creating a ticket or case in the incident tracking system to document activities

- Gathering additional information through interview with or documentation from impacted parties

- Analyzing logs, system configurations, network traffic, and other data sources to identify potential indicators of compromise (IoCs)

- Following proper forensic procedures to collect and preserve evidence for future law enforcement or legal documentation

At minimum, security teams should collect incident data and documentation like:

- Incident details

- Date of alert

- Time of alert

- Affected system/network

- Initial observations

- Logs and alerts from security tools for information about suspicious or malicious activity, including data from:

- Identity and Access Management (IAM)

- Endpoint detection and response (EDR)

- User and Entity Behavior Analytics (UEBA)

- Operating systems

- Network traffic data for insight into anomalies, including data from:

- Intrusion detection system (IDS)/intrusion prevention system (IPS)

- Firewall log data

- Network device

- Data downloads and uploads

- Netflow logs

- System configuration information, including from:

- Vulnerability scanner data

- Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) configurations

- Threat intelligence and IoC information, including from:

- Government alerts, like from the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA)

- Paid feeds

- Vendor vulnerability notices

Containment and Eradication

During the containment and eradication phase, you should engage in the following activities:

- Isolate the threat

- Remove malware

- Delete compromised accounts or account data

- Update vulnerable systems with security patches

Some critical activities include:

- Isolating the affected systems or network from the rest of the environment

- Disconnecting infected devices from the network or disabling their network access

- Reroute or filter network traffic

- Close vulnerable ports and mail servers

- Scanning for malware and removing malicious software or files

- Using a sandbox or system restore to eliminate malware threats

- Identifying compromised user accounts and revoking access rights

- Changing passwords for affected accounts

- Implementing multi-factor authentication for affected accounts

- Identifying exploited vulnerabilities and applying security updates

At minimum, security teams should collect incident data and documentation like:

- Details about containment and eradication activities

- Date and time for each action

- Systems that actions were taken on

- What actions were taken and why

- Record of malware analysis, including:

- Malware type

- Malware behavior

- Remediation activities taken

- Record of remediation activities, including:

- Device or system updated

- Security updates applied to device or system

- Date when security update applied to device or system

- Changes made to user accounts, including:

- Affected user IDs

- Changes to passwords

- Changes to user privileges

- Document communications between team members, including:

- Incident reports

- Emails

- Meeting minutes

- Network and system logs showing containment and eradication activities

Graylog: Streamline Your Incident Response Processes

With Graylog Security, you can use prebuilt content to map security events to MITRE ATT&CK. By combining Sigma rules and MITRE ATT&CK, you can create high-fidelity alerting rules that enable robust threat detection, lightning-fast investigations, and streamlined threat hunting. For example, with Graylog’s security analytics, you can monitor user activity for anomalous behavior indicating a potential security incident. By mapping this activity to the MITRE ATT&CK Framework, you can detect and investigate adversary attempts at using Valid Accounts to gain Initial Access, mitigating risk by isolating compromised accounts earlier in the attack path and reducing impact.

Graylog’s risk scoring capabilities enable you to streamline your TDIR by aggregating and correlating the severity of the log message and event definitions with the associated asset, reducing alert fatigue and allowing security teams to focus on high-value, high-risk issues.